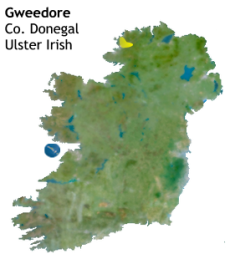

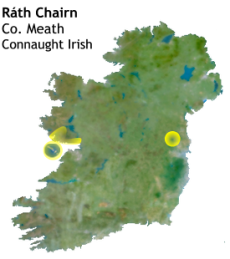

The Gaeilge word for storyteller is seanchaí. The pronunciation of this word varies across the island of Ireland.* These samples are in two of the three major dialects (click on a map to listen):

The earliest stories were told by shamans, whose elocution had the power to inspire hunters to feats of bravery and skill that would enable them to explore new territory, and bring down beasts in sufficient quantity to nourish themselves and supplement the gleanings of their gatherers, back home. Later, the domestication of animals and plants de-emphasized the value of hunting grounds, and changed the significance of soil from simple occupation to legal ownership, because land now possessed the potential to produce food reasonably reliably.

That meant there were more abundant harvests for the picking, especially because fertile territory was likely to be occupied by fertile females. The opportunities for food, frolic and fecundity had increased exponentially. In other words: F³.

Thus, the slings and arrows of heroic hunters became the tools of the most enterprising gatherers, who became known as “warriors;” and in order to stay in business, the shamans had to change their résumés.

Some stayed on as oracles, explaining and encouraging the practice of faith by the community, which now had need of prayer for deliverance from the forces under arms in pursuit of F³. Many became midwives, in response to a burgeoning birthrate aided and abetted by agriculture’s improved nutrition; or barber-surgeons, to cope with the demands of civilized coiffure and the violent and virulent casualties of city living. The bores among them became bean-counters, whose ability to calculate beyond the limits of the digits on hands and feet, enabled them to establish systems of inventory control that led to such civil boons as bureaucracy, law and politics. Still others became the cognitive and cultural caretakers of humanity, in the roles of historians, genealogists, educators, and storytellers.

Ancient Roman literary critics first codified literary conventions, but they had precious little to go by; indigenous Roman literature being almost nonexistent. In analyzing the oldest known books they’d borrowed (which were from the Greek oral tradition, personified by Homer), they declared that there were two kinds of stories: Epics, consisting of war stories, and Romances, consisting of love stories (usually involving the sex lives of the gods).

The enduring stories in any cultural tradition are still the ones about fighting and footsie. Even an icon as apparently innocuous as that of a “Valentine,” carved into a the bark of a tree or adorning a box of chocolate truffles, tells the same tale of turf wars and their ultimate outcome: F³.

Back when the storyteller was the only passive entertainment game in town, a preliterate people’s library was limited to what one human mind could imagine and remember (sometimes aided by rhyme, rhythm or music). With the advent of widespread literacy, the number of available storytellers increased, allowing for a wide variety of stories and the opportunity to specialize in their telling, mainly through the medium of print.

But although the stories have multiplied, they vary only superficially: Whether it’s a Star Wars screenplay, The Lord of the Rings trilogy of tomes, or Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the real tale is still that of territorial – hence genetic – dominance. The survival of the fictional fittest still determines who gets to stock and fish from a story’s gene pool. F³ still rules.

The evolutionary offspring of Roman literary critics include today’s professional reviewers, agents, editors and publishers, who now promulgate literary conventions to suit their agenda (see prior posts about BISAC codes here and here). This agenda involves an attempt to control the marketplace: what kind and quantity of literary Art is sold, for what price, to whom, and where. (This is only human nature, as the literary gurus and gatekeepers fight for their own pieces of the F³ pie.)

Literary conventions do tell potential readers what may be expected, in general, of the different versions (known as “genres”) of the F³ story that are available in the marketplace of Written Art; nevertheless, the boundaries of such expectations must, of necessity, be permeable. For example, the defining outcome of a love story that’s in the “romance” genre of the English literary tradition, eventually evolved from the exclusive and stringently imposed “Happily Ever After,” to include the equivocal but more realistic “Happy For Now.”

But to insist that authors adhere strictly to the conventions of a particular genre (or to suggest that they should limit their production of stories to only one genre), is to inappropriately apply the rules of a Craft to an Art. The genre of a craft depends on the function that a crafted object is intended to serve. The conventions of basketry (coiled, split, wicker, and plaited) are weaving techniques adapted to the material used to make a basket, and their employment is affected by the precise use to which the basket will be put. But a basket is meant to be a porous container: it won‘t hold water, unless an impermeable liner is added to it (such as a layer of clay, or a plastic bag), and even then, it will still be a basket; it can never be a bucket.

In contrast, the purpose of Art is to communicate, and the boundaries between Art forms frequently blur. A painting may consist of so many layers of pigment that it assumes the form of a sculpture in low relief. The words of concrete poetry also evoke a visual image. There can be many layers of significance to a story, and like Irish Firebrands, such a work may cross several genre lines. Writing, as a work of Art, will communicate anything its author wants to communicate, in whatever form or appearance its author chooses to give it.

A proper understanding of literary conventions (Rule #5 of The 7 Reasonable Rules of Writing), is that they can serve as storytelling prompts for writers, and as signposts for readers in search of directions to explore for intellectual and/or emotional reading experiences. But at no time should conventions constrain Artistic creativity. Authors are Artists, free to create what they will, and to cross genre lines at whatever point they choose, whether within the body of a particular work, or across the corpora of their creations.

* This could make seanchaí the origin of the names Chauncey and O’Shaunessey.

Good thought provoking essay. I think the tools, once learned, can be used for whatever purpose the writer chooses. So much about writing can be learned. It’s in the voice, and how the tools are then used to direct the perception of the work that art is created. I hope.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! You’re right about learning to work with the tools. I think we’re often negatively conditioned by the remark, “he’s such a talented …” (plug in your choice of Art), as if the ability to produce Art were wholly a matter of a “gift” that someone else is given, while the rest of us get a bug on the end of a stick. The truth is that we’re all given different creative abilities, and our condemnation will be if we fail to multiply them, even if only to “lend” them to others, to “earn interest,” as we’re counseled in the parable. I take that to mean that even if we don’t feel “talented,” we should actively patronize the Arts, so they can grow. There’s always room for more Art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pretty darn insightful here. Something to really mull over. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

After I made the connection between the symbolism of “Goldilocks” and that of the “Valentine,” I understood the Ares-Eros axis of all storytelling. The value of genre and its defining literary conventions is purely descriptive, but the gurus and gatekeepers try to make it prescriptive and proscriptive. As Writing Artists go, only the Poets have had the gumption to thumb their noses at the micromanaging criticism and psychological control attempted by the people in the ivory tower. Prose Artists need to follow the Poets’ example: to take back our Art, write whatever we please about Love or War, and the Devil can take the hindmost.

Thanks for visiting and commenting!

LikeLike

You raise some wonderful points. I particularly love “But at no time should conventions constrain Artistic creativity” as well as your comparison of a basket to a bucket. I think you’re missing your second calling… Besides writing, you should be giving video webinars about writing. You could definitely make some big bucks! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person